IF YOU WANT IT DONE RIGHT, YOU GOTTA DO IT YOURSELF

Written by Josip Jagic

Photographs by Ryan Loewy for Be-Mag

Drawing a parallel between rollerblading and the do-it-yourself ethics of hardcore punk may have crossed a few people’s minds, and thus, might ruffle a few feathers.

Currently, there exists an on-going desire on the behalf of some of the more prominent people in our community to distance them from what they see as a fabricated rebelliousness of punk rock, in turn advocating the need to make rollerblading more family friendly; a hope that it would make it more palatable to the mainstream audiences and possible sponsors.

There’s no need to claim that rollerblading is equivalent in its demeanor to that of the sounds of Minor Threat, DS-13 or Blitz; a parallel certainly exists in the ethics of creating something of value without corporate money. One keeps on doing it just for the sake of doing what you love, sacrificing other, more lucrative careers to stay true, no matter what.

In a similar route that was taken for punk rock, rollerblading as a sport, or a subculture rather, caught the mainstream eye, but it was only when companies such as Rollerblade and Roces adopted the antics of people like Chris Edwards, Arlo Eisenberg, Angie Walton, Brooke Howard-Smith and so forth, an attempt to cash in on their appeal that only lasted for so long.

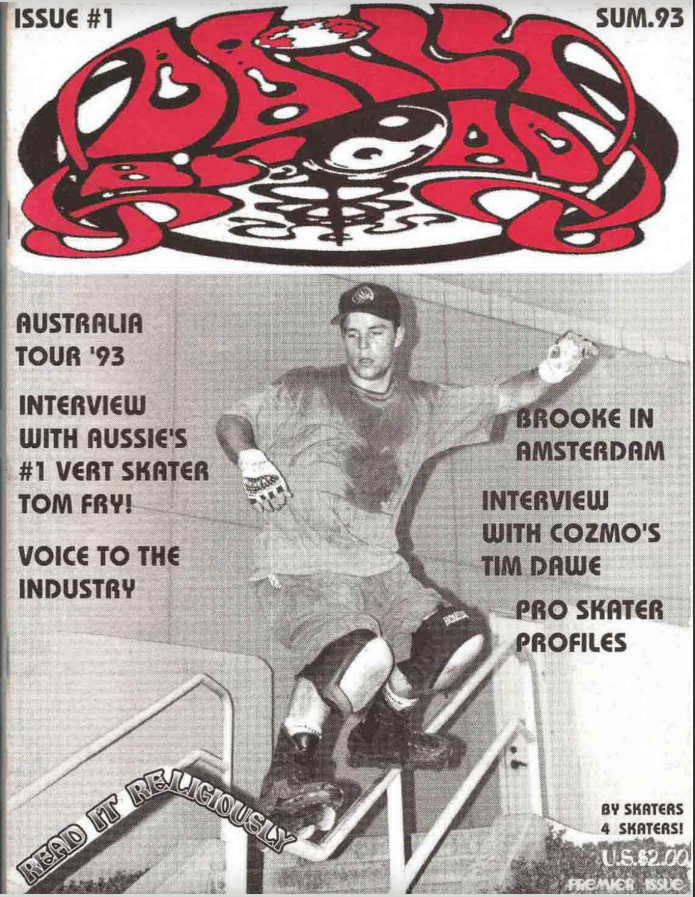

Chris Edwards on the 1st Cover of Daily Bread | 1993 | Image Courtesy of the Blade Museum

It’s easy to see a parallel in a picture similarly painted in the punk scene, when big record labels adopted early UK punk bands such as The Sex Pistols and The Clash, resulting in incredible profits. And for the first couple of years, things were looking up; punk bands toured big venues in the second half of the 1970s, in tandem, rollerblading in the mid to late nineties did the same; there were tours, there was money.

And all of a sudden, in 1980, punk rock was declared dead. Even though the reasons for the decline of both can’t be declared equal, there are some uncanny similarities. While rollerblading suffered from the backlash and the hate campaigns from the skateboarding industry, punk rock was soon pushed out by other greedy corporate music execs. Both felt the effect of if it don’t make dollars, then it don’t make sense.

Abandoned and found to fend for itself, (here’s looking at you Salomon, Bravo Corp, Bauer, Levi’s, continue the list yourself), punk rockers were left to their own devices, as were skaters after their dismissal from the X Games.

Photograph by Ryan Loewy for Be-Mag

So what is one left to do?

The punk rockers started creating their own music labels.

Rollerbladers started making their own clothing and product.

There were no concerts or shows dedicated solely to punk, so they were created.

There was no genuine means of judging or promoting street skating, so Jon Julio created the IMYTA.

Punk rockers made their own videos. And in similarity, rollerbladers found ways to document and record their place in history with the likes of Daily Bread and Videogroove.

Fed up with waiting for others to build a scene for them, it’s best to look at the West Coast in the late 70s and early 80s. Greg Ginn was already in his mid-20s when he started SST Records, in an effort to cut and put out records by his little band called Black Flag, which would come to be regarded as the godfathers of American hardcore punk music.

Another great example is Brett Gurewitz, founding member of the band Bad Religion, who started Epitaph Records, today a global juggernaut, regarded as one of the most important independent labels, with a huge roster of bands and one of the staples of the Warped Tour; one of the longest lasting music tours.

At one point, Black Flag realized they’d have to be on the road the whole time to make it, if they were ever to make it. Similarly, rollerblading today, in comparison with American punk rock, never really took off, regardless of the relatively large number of small scenes existing in the US from coast to coast; to be able to continue doing it, you had to take a page from Adam Johnson’s book; get in the van and try to play wherever they wanted you to play.

And thus paving the way, they also showed the way, coming to terms that they might not make it big, but that it still made sense to do it.

Rollerblading has its own DIY hardcore punks. Shit, at today’s numbers, be it participation or actually trying to run a company and making it stay afloat, it’s almost all DIY.

Photograph by Ryan Loewy for Be-Mag

Ever since he started making videos, in turn then starting Vibralux, along with Street Artist and Dead, Adam Johnson’s knack of getting people in the van and traveling all across the US to film with some of the best people to ever put on skates, there’s no further testament than the videos he’s made to solidify his dedication to the sport. Doing it on his dime and time, for him it has, and continues to be worth the sacrifice. As Black Flag’s albums defined hardcore punk, AJ’s videos defined true street rollerblading.

Working on Valo for 15 years, Jon Julio managed to almost singlehandedly redefine what rollerblading styles are and what is possible in terms of creating your own vision, even with the limitations of working with partners that don’t necessarily share the same vision. With Them Skates, once again Julio has invested his all into rollerblading.

Photograph by Ryan Loewy for Be-Mag

The route of independence brings challenges, though, and not everyone has had a fairytale ending. Take for instance the cases of Jon Elliot‘s, Shima‘s and Jan Eric Welch‘s Rat Tail Distribution. Brands such as Vicious, 4X4, NIMH and then later SSM, were the epitome of punk rock, but did not have the same path as its peers, joining a long list of similar acts. Similarly, this fate would be prescribed for more than a few once influential and big bands or record labels in punk rock.

Jan Welch | Portrait by Ryan Loewy for Be-Mag

But while they were there, they made a difference and will be remembered as ground breaking. The history of failed record labels in punk rock is at least 25 times longer than the list of failed rollerblading companies, but each of their instances was a desire, a sense, a need to try, and more importantly, inspire others that it still makes sense to try.

It makes sense to get in the fucking van, to go film with your friends, to make videos, to travel to compete; it will make you better people, you will meet friends that will hook you up with a place to sleep even though you have never met them before in your life. Like playing punk rock at shitty back alley venues, it will make for stories, lifelong memories and books.

So, do we need big companies and huge competition series like the X-Games or FISE to help our best athletes make more money and make a living out of it, as some thought punk bands needed major labels? Yes, they would be nice to have.

But we need to fight.

We need to fight for our place in the spotlight.

We need to fight for the money for the Haffey’s, the CJ’s, the Atkinson’s, the Pottier’s, the Finnochiaro‘s and all the other incredible competition skaters who catch the eye of even the most blasé and indifferent.

Regardless, we’re in a good place even without those.

Rollerblading is authentic, it’s raw and it’s worth it.

The big competitions are fine, but even without them, people like AJ, like the Anthony brothers, like the people running the smaller wheel brands, running the shops, running independent boot companies, they will continue to do their own thing and rollerblading will thrive. It will probably never see itself again at the mid 1990s levels, but as long as there are people creating the events, doing the tours, filming the videos, putting out mags or writing (shameless Be-Mag plug), making soft goods or hardware, or just skating and trying to create a scene with their friends,

there will be rollerblading.